The Face of Mona Lisa

For more than 500 years, the most famous and mysterious picture in the world remains the portrait of the Mona Lisa, otherwise known as La Gioconda, by Leonardo da Vinci. The word mona is an abbreviation for the word Madonna, which means “my lady” (mia donna). It is believed that Mona Lisa was the 24-year-old wife of the Florentine silk merchant Francesco Giocond, after the artist and historian Giorgio Vasari described this picture in detail in his book Biographies (Le Vite), in 1560. People often talk about her mysterious smile. Frankly, I don‘t understand this – a smile like any other, I feel nothing special about it. Vasari wrote that while Leonardo worked on this portrait – to make sure that Mona Lisa was not bored – he hired musicians, dancers, and other entertainers. She liked them very much, so why wouldn‘t she smile? There is no mystery here.

But besides the “mysterious smile,” other more intriguing questions remain about that great work of art, thus people still don‘t stop talking it. Some suspect that in reality Leonardo did not depict Mona Lisa, but rather painted himself in a female guise. Some others suspect that it was his mother who was painted there. However, no compelling arguments were given to support these thoughts. In this article, I propose my version of the mystery of whose face is painted in this portrait. But first, let‘s recall some facts.

But besides the “mysterious smile,” other more intriguing questions remain about that great work of art, thus people still don‘t stop talking it. Some suspect that in reality Leonardo did not depict Mona Lisa, but rather painted himself in a female guise. Some others suspect that it was his mother who was painted there. However, no compelling arguments were given to support these thoughts. In this article, I propose my version of the mystery of whose face is painted in this portrait. But first, let‘s recall some facts.

- La Gioconda was a commissioned work, which Leonardo began in 1503 at a time when he was rather tight on money. It was his unfortunate habit of being quite inaccurate with the terms of the agreements, so he did not finish the painting on time and, therefore, was not paid for it. Alas, strangely enough, even though the money was not paid and the contract was rescinded, he very diligently continued working on the portrait for at least four more years, and according to some sources, even for thirteen years!

For some strange reasons, Leonardo never wanted to part with this painting – a rather unusual attitude toward a hired work. Even during the long periods of his wanderings from place to place, he always had the picture with him and kept it close to him, just as a revered icon. Towards the end of his life, despite his poor health (he was partially paralyzed), he took the portrait with him on his final exhausting trip to France, traveling on a donkey through the mountains. When he arrived and settled near Amboise, he flatly refused to sell the painting to his benefactor and admirer, the King of France Francis I. He just promised that the king could take Mona Lisa only after the death of Leonardo. Some paranoid attachment to his own work!

For some strange reasons, Leonardo never wanted to part with this painting – a rather unusual attitude toward a hired work. Even during the long periods of his wanderings from place to place, he always had the picture with him and kept it close to him, just as a revered icon. Towards the end of his life, despite his poor health (he was partially paralyzed), he took the portrait with him on his final exhausting trip to France, traveling on a donkey through the mountains. When he arrived and settled near Amboise, he flatly refused to sell the painting to his benefactor and admirer, the King of France Francis I. He just promised that the king could take Mona Lisa only after the death of Leonardo. Some paranoid attachment to his own work!- French researcher Pascal Cott has studied this painting in the Louvre for nearly 10 years, using the most modern technologies. He found that under dozens of layers of the paint, there is another face of Mona Lisa that is completely different from the woman depicted on the surface. Kott came to the conclusion that the hidden face is indeed the real Mona Lisa Gioconda, while the face that everyone can see on the surface is a completely different woman. Who was she? Perhaps the strong affection that Leonardo felt was not toward the painting, but rather to the face shown on it?

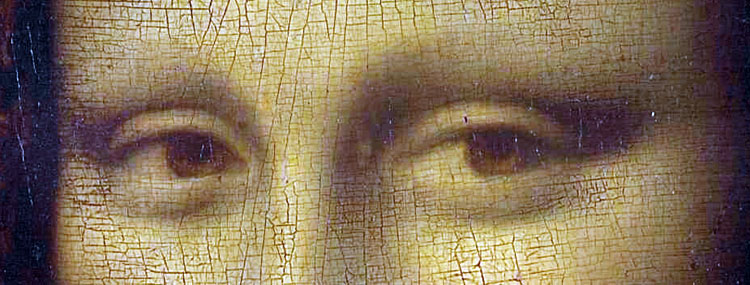

- If you look closely at the face of Mona Lisa, you may notice that she has absolutely no eyebrows or eyelashes. Quite strange indeed! When Kott conducted his research, he found just one tiny hair drawn on the eyebrow. However, the same Vasari, while describing this picture, gave us a detailed description: “… Eyelashes made like the way hairs actually grow on the body, on some places they are thicker, and on some others are less so, and with the corresponding skin pores, and they could not be depicted more naturally… “It sounds like he was talking about some other picture. Most likely, he himself did not see the Mona Lisa. Leonardo died when Vasari was a child, and when he grew up, Mona Lisa was in possession of the French king to whom Vasari hardly had access. Most likely, he did his description from the words of someone else who saw Leonardo working on the first version of the picture that is now hidden under many layers of paint.

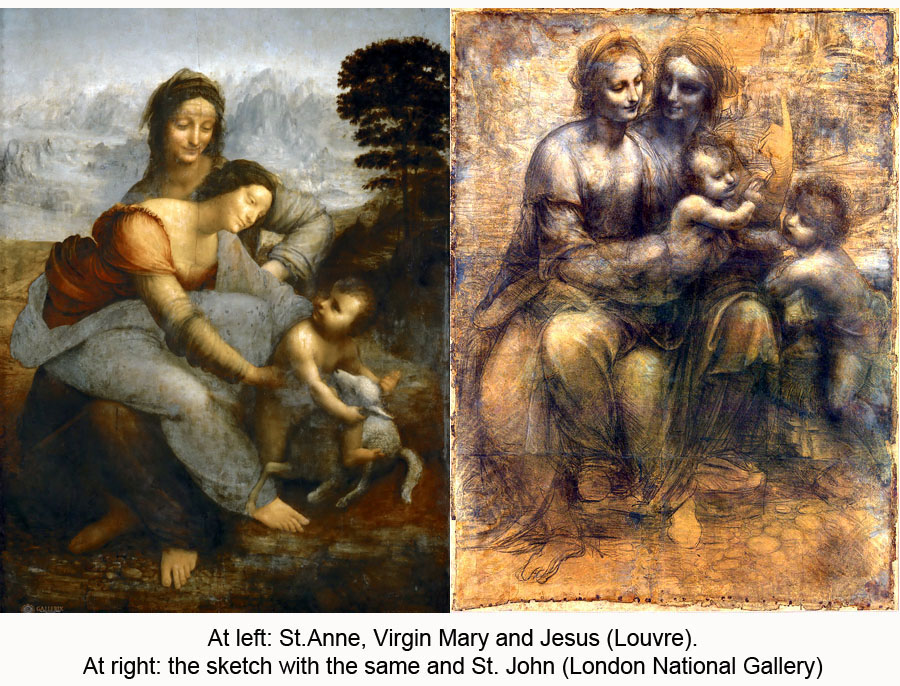

In the same year of 1503, when he worked on Mona Lisa, Leonardo was commissioned a painting for the altar in a Florentine church. It should have depicted the Virgin Mary, her mother St. Anne, and the baby Jesus. He made this painting and now, like the Gioconda, it is in the Louvre. From my point of view, this particular picture is much more mysterious than Mona Lisa. The most incomprehensible thing about it is the composition. The painting depicts the adult Virgin Mary (she must be 18–20 year old – a mature age at those ancient times), sitting like a child on the lap of her mother, St. Anne. Baby Jesus is trying to get away from his mother to play with the lamb. Never before or after has any artist ever portrayed an adult Virgin Mary sitting on the lap of her mother, who would have been 40–45 year old – an elderly woman by the standards of antiquity. Apparently, by doing so, Leonardo had some hidden meaning, that remains quite a mystery to us.

In the same year of 1503, when he worked on Mona Lisa, Leonardo was commissioned a painting for the altar in a Florentine church. It should have depicted the Virgin Mary, her mother St. Anne, and the baby Jesus. He made this painting and now, like the Gioconda, it is in the Louvre. From my point of view, this particular picture is much more mysterious than Mona Lisa. The most incomprehensible thing about it is the composition. The painting depicts the adult Virgin Mary (she must be 18–20 year old – a mature age at those ancient times), sitting like a child on the lap of her mother, St. Anne. Baby Jesus is trying to get away from his mother to play with the lamb. Never before or after has any artist ever portrayed an adult Virgin Mary sitting on the lap of her mother, who would have been 40–45 year old – an elderly woman by the standards of antiquity. Apparently, by doing so, Leonardo had some hidden meaning, that remains quite a mystery to us.- This painting with St. Anne is largely based on the preliminary sketch that is now in the London National Gallery. Leonardo made this sketch according to various accounts sometime between 1490 and 1499, that is, when he lived in Milan and his mother visited him. The sketch differs from the picture in the Louvre – instead of a lamb there is a child – the cousin of Jesus, that is, John the Baptist. But here we have the same strange composition, where the adult Virgin Mary sits on her mother‘s lap.

- Caterina, Leonardo‘s mother, was a young peasant woman who gave birth to Leonardo out of wedlock, with Piero da Vinci. That‘s all that was known about her for a long time. But just recently it was discovered that Caterina was a slave, probably of Arab descent, brought to Italy most likely from Constantinople. She was baptized and received the Christian name Caterina. She was owned by a widow who gave her to Piero in exchange for a house. Piero freed her and three months after Leonardo‘s birth, he married Caterina out to a local peasant.

- Leonardo lived with his mother until the age of four and was affectionately attached to her. After that, he was taken to live with his father, Piero da Vinci. His barren wife wanted a child and Leonardo became her adopted son. So, as a child he apparently had two loving mothers, but until the end of his days he retained most tender feelings and affection for his natural mother. When Caterina was already over 60, he brought her to stay with him in Milan, where she likely died, in 1495. It seems that she was the only woman to whom Leonardo ever felt affection and tenderness. I don‘t at all suspect he had an Oedipus complex, yet it is obvious that he loved his mother very much, and there were never any other women in his life. As Sigmund Freud wrote more than a hundred years ago, “…And therefore, perhaps Leonardo‘s life was so poorer in love than the lives of other great people and other artists. It appears the violent passions, sweet and devouring did not seem to affect the best of his experiences.”

Now, let‘s talk about the hypothesis – who is depicted in the Mona Lisa? I want to reiterate: this is just a theory, the evidence of which will most likely never be found.

The death of his mother in 1495 deeply saddened Leonardo and when he conceived and began sketching a new picture where the baby Jesus was to be depicted with his cousin John, the Virgin Mary, and grandmother Anne, he decided to immortalize his mother by giving St. Anne the face of Caterina. Like many geniuses, Leonardo was a deeply lonesome individual and his mother was the closest person to him. He cherished tender memories of his childhood when a loving mother held him on her lap. Therefore, he decided to put Mary on St. Anne‘s lap, symbolizing the close connection between the mother and her daughter. This large sketch was drawn on eight sheets which were glued together, but Leonardo never made a painting from it because, as usual, he was distracted by other projects. In 1499 when the French occupied Milan, Leonardo‘s benefactor, the Duke of Sforza, fled the city. Leonardo followed suit, left Milan, and after long wanderings through the Italian city-states, settled again in Florence.

There, in 1503 he began painting a portrait of Lisa Gioconda, who just recently had become a mother. This deeply affected him; Childhood memories surfaced and he felt an emotional connection between the young mother and his own mother. It‘s possible that these feelings hindered and hampered his work, but he nevertheless continued to paint her portrait. When all the terms of the contract were elapsed, Gioconda‘s husband was furious and declared that he had no intention waiting any longer and refused to pay. The unfinished picture was left with Leonardo and he decided to change Lisa‘s face, making it the face of his own mother, as he remembered her from childhood. By that time, Caterina had not been alive for many years, so he painted her face from memory – a long and emotionally painful process, since no photography was available in those days. The more he worked on the portrait, the more he attached himself to his young mother in that picture and could never part with it.

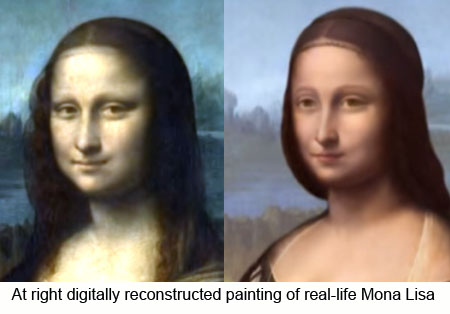

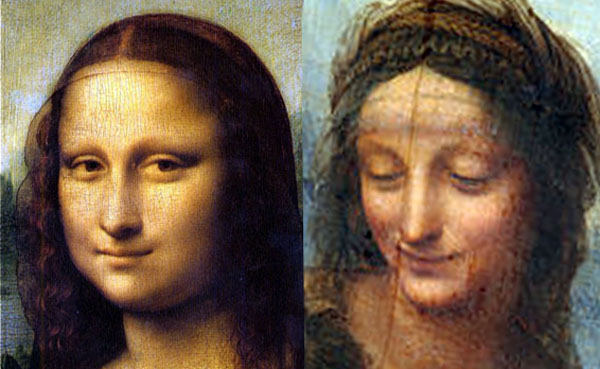

In the same year as when he worked on the Mona Lisa, Leonardo was commissioned a picture of St. Anne, her daughter, and her grandson Jesus. For this painting, he decided to use the old sketch he made in Milan some years before. There, St. Anne had the face of his mother. And again, as with Mona Lisa, he painted his mother, yet at a more mature age, and as Mona Lisa, he worked on it from memory. Thus, he eventually made two portraits of his mother – young and elderly. This gives us an opportunity to compare these pictures. If we put them side by side and adjust the angle of rotation and sizes, it becomes quite clear that they show the same woman, although at different ages. Thus, it can be assumed that in La Gioconda Leonardo da Vinci depicted his mother Caterina at a young age.

In the same year as when he worked on the Mona Lisa, Leonardo was commissioned a picture of St. Anne, her daughter, and her grandson Jesus. For this painting, he decided to use the old sketch he made in Milan some years before. There, St. Anne had the face of his mother. And again, as with Mona Lisa, he painted his mother, yet at a more mature age, and as Mona Lisa, he worked on it from memory. Thus, he eventually made two portraits of his mother – young and elderly. This gives us an opportunity to compare these pictures. If we put them side by side and adjust the angle of rotation and sizes, it becomes quite clear that they show the same woman, although at different ages. Thus, it can be assumed that in La Gioconda Leonardo da Vinci depicted his mother Caterina at a young age.

This hypothesis can be evolved even further. If St. Anne is Caterina, then St. Mary, who is sitting on her lap, is none other than Leonardo herself. Hence, in this picture he placed himself on the lap of his mother, just like a child. By doing so, Leonardo could draw mental parallels between himself and the Virgin Mary: they were both virgins, they both had divine blessings – she had to bring up the Savior, he had to create science and inventions. Neither the Savior nor his creations were understood and accepted by people at those times.

Unfortunately, only a few images of Leonardo exist and he is depicted in all of them with a beard. Thus, it is not easy to compare his face to the face of the Virgin Mary in the picture, where she sits on the lap of St. Anne. Still, it is worth trying and placing two portraits next to each other, equalizing their sizes and adjusting the angles of rotation. For the portrait of Leonardo, I chose a relatively recently found one, called the Lucan Portrait. With a certain amount of imagination, you can see a clear similarity, especially in the forms of the nose and lips. If I am right, then the portrait of the Virgin Mary is the only existing self-portrait of Leonardo without a beard, although somewhat feminized.

Unfortunately, only a few images of Leonardo exist and he is depicted in all of them with a beard. Thus, it is not easy to compare his face to the face of the Virgin Mary in the picture, where she sits on the lap of St. Anne. Still, it is worth trying and placing two portraits next to each other, equalizing their sizes and adjusting the angles of rotation. For the portrait of Leonardo, I chose a relatively recently found one, called the Lucan Portrait. With a certain amount of imagination, you can see a clear similarity, especially in the forms of the nose and lips. If I am right, then the portrait of the Virgin Mary is the only existing self-portrait of Leonardo without a beard, although somewhat feminized.

Look at these four faces (Mona Lisa, St. Anne, Virgin Mary and Leonardo) – don‘t you think that they are the images of close relatives – a mother and son?

Jacob Fraden is an inventor, entrepreneur, educator, artist and writer. He holds degrees of MSEE and Ph.D. in medical instrumentation. Among his 60 inventions are the Instant Ear Thermometer, Smartphone with Infrared Thermometer, Motion Controlled Light Switch, and Home Blood Pressure Monitor. Dr. Fraden is the author of a bestselling “Handbook of Modern Sensors” (five updated editions since 1994) that is the principal textbook on sensors used by many major universities worldwide. He authored over 100 technical and scientific papers and book chapters. He published in English a book of short stories “Adventures of an Inventor” and also writes short stories in Russian and English. He lectures in University of California, San Diego, on theory and practice of sensors and history of the Renaissance Art.

By Jacob Fraden