Tale and Craftsmanship of a Shofar

Spending Erev Rosh Hashana (the evening of the Jewish New Year) in Israel is a truly unique experience. The sounds of shofars greeted me from every corner as I strolled along the streets of Tel Aviv. Tekiah, shevarim, teruah, tekiah gedolah – loud, mesmerizing, vibrating, and hypnotizing sounds – they announced the beginning of the New Year, […]

Spending Erev Rosh Hashana (the evening of the Jewish New Year) in Israel is a truly unique experience. The sounds of shofars greeted me from every corner as I strolled along the streets of Tel Aviv. Tekiah, shevarim, teruah, tekiah gedolah – loud, mesmerizing, vibrating, and hypnotizing sounds – they announced the beginning of the New Year, as an overture to the honey sweet future we all hope and pray for.

According to Jewish tradition, the shofar is blown before, during, and after the Musaf prayer on both days of Rosh Hashana. It is also blown once to mark the end of the fast on Yom Kippur and the green light for the family’s avalanche move to the dining room table.

According to Jewish tradition, the shofar is blown before, during, and after the Musaf prayer on both days of Rosh Hashana. It is also blown once to mark the end of the fast on Yom Kippur and the green light for the family’s avalanche move to the dining room table.

The city’s great shofar blowout ignited the inquiring mind in me to find out where these shofars come from. To my pleasant surprise, I learned that authentic and kosher shofars do not come from China! With a bit of Google searching and a friendly chat with the Dan Hotel’s concierge, the professional secret was unveiled: ‘’The Eli Ribak factory shop on Nahalat Binyamin Street in Tel Aviv.’’

The city’s great shofar blowout ignited the inquiring mind in me to find out where these shofars come from. To my pleasant surprise, I learned that authentic and kosher shofars do not come from China! With a bit of Google searching and a friendly chat with the Dan Hotel’s concierge, the professional secret was unveiled: ‘’The Eli Ribak factory shop on Nahalat Binyamin Street in Tel Aviv.’’

‘’It is the biggest and Israel’s best shofar-making factory in the world,’’ assured my now-best friend at the hotel’s desk.

‘’It is the biggest and Israel’s best shofar-making factory in the world,’’ assured my now-best friend at the hotel’s desk.

Apparently many people visit the place, try out the sound, and some even purchase a shofar as a gift to bring home to California, as in my case. But its main customers are the professional shofar blowers designated by their communities or their synagogues as the messengers of the familiar sounds in honor of the High Holidays.

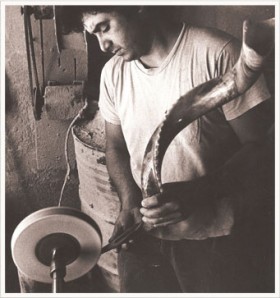

Eli Ribak, who runs the shofar company and whose family has been in the business of producing shofars, or as he calls them, ‘’the instruments made from animal horns,’’ has been doing it for three generations. The advantage of buying the shofars directly from Ribak’s, rather than from Judaica shops, is that he offers a custom-made fit, adjusting the shofar opening to suit a particular size of mouth.

Eli Ribak, who runs the shofar company and whose family has been in the business of producing shofars, or as he calls them, ‘’the instruments made from animal horns,’’ has been doing it for three generations. The advantage of buying the shofars directly from Ribak’s, rather than from Judaica shops, is that he offers a custom-made fit, adjusting the shofar opening to suit a particular size of mouth.

On display in Ribak’s tiny shop are shofars in all shapes and sizes. There are those made from ram horns imported from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. (Since Israel has no diplomatic relations with Algeria and Tunisia, the stock from those countries is sent via Morocco). There are also shofars made from antelope horns imported from South Africa.

On display in Ribak’s tiny shop are shofars in all shapes and sizes. There are those made from ram horns imported from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. (Since Israel has no diplomatic relations with Algeria and Tunisia, the stock from those countries is sent via Morocco). There are also shofars made from antelope horns imported from South Africa.

Today, the shofar is a powerful symbol of Jewish culture in Israel and around the world. Each Jewish community in Spain, North Africa, Holland, Italy, Poland, Yemen, Iraq, and Israel has a certain shape and sound of shofar appropriate for its people.

Blowing the shofar is an inseparable part of the atmosphere of the High Holidays and adjustment of the sound whether it be thick, raw, thin, or weeping, is also a professional secret. It is a complicated and intricate craft, full of secrets and mystery. Except for minor changes, shofars have been made in the same way for many years, and it seems that electronic machines will not replace the craftsmen in the near future.

Prices range from tens to hundreds of shekels. The more elaborate, bejeweled shofars can fetch upwards of hundreds and even thousands of shekels. In recent years, with tens of thousands of Chinese Christians coming on organized pilgrimages to Israel, the shofar has become a must-have on many of their shopping lists. They love bringing back Judaica as souvenirs, so what better piece of Judaica than a shofar?

A bit of trivia: More than 1,000 people gathered this year at a New Jersey Jewish institution to break the Guinness World Record for largest shofar ensemble. The participants blew together on the shofars for five minutes to break the previous shofar ensemble record which was held by Swampscott, Massachusetts, which blew 796 shofars on the beach in 2006.

Shana Tovah and Happy New Year!

Photos courtesy of the Ribak Shofar factory.

Lina Broydo immigrated from Russia, then the Soviet Union, to Israel where she was educated and got married. After working at the University in Birmingham, England she and her husband immigrated to the United States. She lives in Los Altos Hills, CA and writes about travel, art, style, entertainment, and sports. She hardly cooks or bakes, not the best of ‘‘balabostas’’ her beloved beautiful Mom, Dina, was hoping for. Therefore, she makes reservations and enjoys dining out.

By Lina Broydo